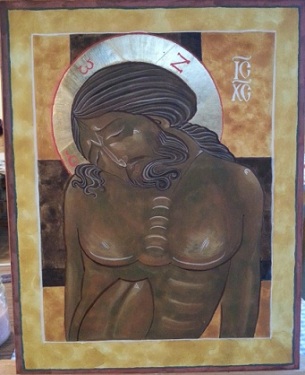

An icon is always completed with a name. Its a little bit the way small children write (or ask their teacher to write) a little label beside their picture to distinguish one collection of blobs and lines as mummy. Even a bad icon is an icon when it has a name. The name was also the prerequisite for having the icon blessed by placing it under the altar during the service.

We also added the outlines, the final light on the body, and the extravagantly highlighted hair:

What was a picture is now an icon; Christs human body, still somewhat naturalistic until today, is now enclosed in a stylistic framework which distances it from the ordinary. I feel it has lost some of the subtlety of human emotion, but it has gained something of the eternal.

The thing people always say about icons is they look at you even that their eyes follow you. It is not a simple subject-object encounter but subject-subject. But the odd thing about this icon, taken of course from a Western model, is that the eyes are closed. In fact it has been said that this is the earliest depiction of Christ dead.

So in a way we have the opposite of an encounter with the presence of Christ; we have an encounter with his absence. During Passiontide, in the West anyway, we veil images or turn them to the wall. This is the iconographic equivalent; it allows us to experience not a moment of closeness but a moment of deprivation, of desolation. Yet in another way Christ has never been closer to us than in this most human of all moments, of vulnerability and death.

I believe I may have inadvertently promised you a poem. So here is one not made under supervision or based on any masterpiece, but just a personal reflection on the intimacy and distance of the painters encounter with the icon.

For an absent friend

I touched your cheek today, my friend

You had already gone.

Your golden skin, once bruised by reeds,

now turned

imperishable as memory

and the conservators art.

Today I met you, long companion

for the first time, now

face to face, after a sojourn of seven days,

and I knew you

as a mother knows her unborn child.

Your eyes

where love would keep my miniature

are dark, and gaze on distant galaxies.

Where you have gone, I cannot follow.

And yet today

I smoothed your brow, tender

with sable, and with agate

burnished a pillow for you

to lay your hair

the way you would have liked it.

Here I can be

close as breathing

to the space where you are not

and gaze as though my hungry eyes could eat

the interposed aeons

and bring the lips which smiled before the stars were lit

to mine

which press now on an absence and a gilded board.

You are going to get very familiar with this face.

You are going to get very familiar with this face.